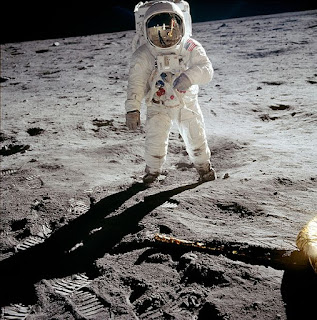

Tokina's 100 f2.8 ATX-PRO Macro is an excellent choice for both digital and FF/film shooters.

When looking at extreme close up (macro) photos, two reactions are quite common: “that's cool!” and “how can I do that?” Well, macro photography is undeniably cool (but challenging) and as for how to do it, the answer is simple: buy a macro lens.

Okay great, what is a macro lens?

Technically speaking, macro lenses are lenses that can focus to extremely close distances, so close that they will reproduce the subject on the film/sensor at its true life size. In photographer jargon, being able to do this gives a lens either a 1:1 reproduction ration or a 1.0x life size magnification, both of which mean the same exact thing. To put it in a visual term, if you shot a macro shot of a penny on a film camera, Lincoln's head would be the same size on the negative that it is in real life.

As for what types of macro lenses are out there, there are two common sizes: the 100mm f2.8s and the 200ish f3.5s, though there are other focal lengths on the market, too, some as short as 35mm. The good news about buying a macro lens is that, because of the demanding nature of macro photography, one would be hard pressed to find an optically bad macro. Generally speaking, macro lenses are sharp to diamond dust saw sharp from widest aperture across the entire frame and virtually free of distortion. The bad news: because macro lenses are such precision optics, their price reflects the workmanship. A macro lens will typically sell for at least $400 (the 200mm f4 Micro Nikkor is nearly $1,800 new).

With a macro lens, the minimum focusing distance is something that needs to be considered. As with all lenses, minimum focus distance is measured from the film/sensor plane to the subject, not end of lens to subject. So, if you have a 100mm macro lens with a minimum focus distance of 11 inches, the subject will actually be about only 6 inches from the front of your lens. Needless to say, longer is better because, the closer you get, the more of your own light you block (and the more timid insects you scare away). While there is no fix for scaring subjects, the light situation can be remedied not with expensive macro lighting rigs, but with white paper used to reflect light onto your subject.

Unfortunately, there are a lot more “macro” lenses than the 1:1 variety.

Whether you choose to call it a marketing tool or deceptive advertising, manufacturers in all industries often like to stretch the capabilities of their products to the breaking point. Photographic companies are no exception. One of the biggest stretches comes in the area lenses and specifically, their close-up capabilities.

To put it simply, unless the lens can do a 1:1 reproduction ratio or a 1.0x magnification factor, it is not a macro, sorry. Unfortunately, this traditional definition of macro seems to be disregarded most of the time today.

Even in the old days, manufacturers were willing to stretch the definition of “macro” to its limit. To find proof of this, look on KEH's website for manual focus/early AF macro lenses. Chances are that a lot of them will only give 1:2 reproduction or .5x magnification (half life size), you pick your terminology. Why the macro designation? Simple, with a dedicated extension tube, all such lenses are capable of true macro photography. The reason such lenses were sold was to appeal to the poor macro shooter. A 1:2 “macro” plus extension tube was cheaper than a true macro.

Unfortunately, come 2011, things have gotten far, far worse. Now, manufacturers are willing to label anything around a 1:3 reproduction or a 0.3x magnification power as a macro. Yes, while a lens of these lesser closeup powers can be somewhat useful, they pale in comparison to dedicated macro lenses. On top of that, most of these “macro” lenses are zooms, which means that, unlike a dedicated macro prime, that can be optimized for a single focal length, they will often be soft and anything but sharp across the entire frame, even when stopped down. On top of this, there are all kinds of thread-on “macro filters” out there, none of which can both turn your standard lens into a true macro while retaining dedicated macro lens quality. Below, you'll find a list of true 1:1 Macro Lenses.

Third-Party:

Tokina 35 f2.8

Tokina 100 f2.8

Tamron 60 f2 VC (crop only)

Tamron 90 f2.8

Tamron 180 f3.5

Sigma 70 f2.8

Sigma 105 f2.8

Sigma 105 f2.8 OS

Sigma 150 f2.8

Sigma 150 f2.8 OS

Sigma 180 f3.5

Manufacturer:

Canon 60 f2.8 (Crop only)

Canon 100 f2.8

Canon 100 f2.8L IS

Canon 180 f3.5L

Nikon 40 f2.8 (crop-only)

Nikon 60 f2.8

Nikon 85 f3.5 VR (crop only)

Nikon 105 f2.8

Nikon 105 f2.8 VR

Nikon 200 f4

Olympus Zuiko 50 f2 (crop-only)

Olympus Zuiko 35 f3.5 (crop-only)

Panasonic-Leica 45 f2.8 Macro Elmarit (crop-only)

Pentax smc DA 100 f2.8 WR

Pentax smc DA 100 f2.8

Pentax smc DA 50 f2.8

Pentax smc DA Limited 35 f2.8

Sony 100 f2.8 Macro SAL

Sony 30 f2.8 DT Macro SAL SAM (crop-only)

Sony 50 f2.8 Macro SAL

Sony 30 f3.5 SEL (E-Mount, crop-only)

Moral of the story: be sure to read the fine print, not just the key features when buying a lens as, more often than not, macro is no longer macro today.

For more info:Macro Photography Primer

Humble requests: